Chris Francis Kealley.

The Experiences of

WX 713 PRIVATE CHRIS FRANCIS KEALLEY

2nd 11th Battalion 6th Division

10th November 1939 to 22nd December 1945

WAR SERVICE RECORD

Christopher Kealley

Prior to World War II I was farming. I enlisted on the 10th November 1939. Two thousand two hundred and thirty days later (2230 days) later I went back farming.

I had joined up in Katanning after a recruitment drive. We were sent by train to the Northam Camp, Western Australia, where we joined the 2/11 Battalion. After a period of training at Northam we then went to Greta New South Wales via Macquarie Island on the ship ‘SS Katoomba’. We sailed on this route to stay off the main shipping lines, which were patrolled by enemy submarines, but I doubt if they would have hit us as the seas were too rough.

I spent my first Christmas away from home in Newcastle NSW. During these travels I have fantastic memories while waiting for transport to Ingletown of looking out from a high position over Sydney after dark and seeing all the lights and neon signs. This boy from the bush had never seen the likes of it.

Next, we were sent back across the Nullarbor to Perth for about a week of pre-embarkation leave. We left for the Middle East on the 20th April 1940. We were aboard the old troop ship from the first World War the ‘Nevassa’, commonly referred to as ‘Never Was Ship Like This Before.’ The Nevassa was a troop ship before World War I and was due to be scrapped. She was recommissioned for the 1914-1918 show and was again due for the scrap heap in 1939. She still had 75% of the original crew on her and from the taste and smell the food was taken on board when she was first launched.

We arrived at camp at Kilo 89 in Palestine and from there we went to Borg El Arab just out of Alexandria where we spent Christmas 1940. We moved from Borg El Arab to Mersa Matruh where we had our first taste of what it was like to face the enemy. The Italians were pushed back to Benghazi and the 9th Division took over from us. We were returned to Alexandria where we embarked for Greece going north as far as Mount Olympus where we were forced to fight a rear-guard action right down to Crete being dive-bombed practically all the time. The trip across to Crete was woeful. We were forced to surrender at Retimo after fighting.

Then followed four years of being a prisoner of war. For about the first fortnight we lived on rice, olive oil and cheese made from goats’ milk and molasses. From Crete we were taken by small fishing boats to Salonika with our only food which was uncooked salted fish. Several weeks we spent in the old Turkish barracks from the First World War. The old POW compound was still standing nearby. We were kept busy fighting hunger, bed bugs and lice. On the days we were issued with horse beans a cockroach was considered a lucky bonus in vitamins.

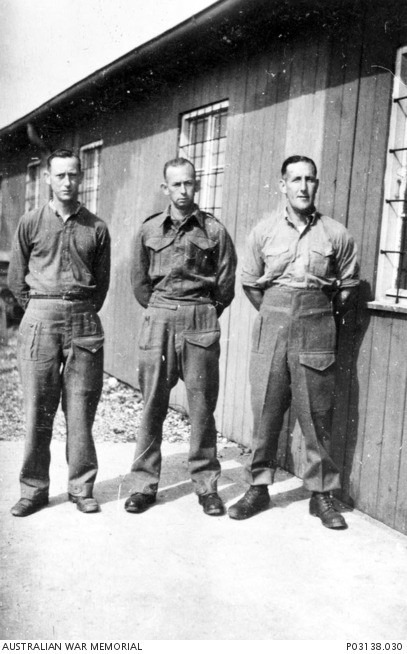

MUNICH, 1942.

Group of Australian Prisoners of war at Berg Am Laim. German guards at rear.

Finally, we were put on a train to Munich in Germany. Accommodated in closed in cattle trucks which held 10 horses or 40 men. The only ventilation was a 50cm x 20cm gap with barbed wire nailed to it to prevent anyone squeezing through. Our only toilet was a 1 kilo meat tin which had to be juggled between the barbed wire to be emptied. The stench was vile but fortunately I did not have a spot near the ventilator. This trip lasted six days with the only break of about one hour at Belgrade where the Red Cross gave us beech tea and bread. The Red Cross were our saving grace throughout our imprisonment. The parcels they sent included such items as tea, coffee, tinned meat, fish, milk, butter or margarine. Margarine was preferred as the butter was often rancid. There were also biscuits, dried fruit, chocolate, custard powder and sometimes cigarettes in the parcels. The parcels weighed 10 pounds and were issued once a fortnight and once every 12 months we were allowed one clothing parcel from home. With these extras we were able to barter with the locals for such things as bread, salt, vegetables etc. Without them we would have starved as did a lot of the Russian prisoners who had no such help.

Left – Informal group portrait of three Australian mates standing outside one of the wooden buildings, about to go out on a work party from the prisoner of war (POW) at Stalag VIIA in Moosburg.

Identified right VX22676 Corporal (Cpl) Nathaniel John Spencer, of 2/8th Field Company, of Alphington, Vic. Cpl Spencer enlisted on 5 June 1940 and was captured on Crete, and became a prisoner of war in Stalag VIIA at Moosberg, Germany for the duration of the war. Cpl Spencer was the youngest of five Bailey Spencer brothers who fought in the First and Second World War.

Our compound was at Mooseberg just out of Munich. We were there for about six weeks before being sent out on working parties. I was working for the council doing asphalt work. Christmas 1941 was spent in West End Camp with thirty-six men to a 6 x 9 metre room and a minus 40 degrees. We were then moved to Waldfriedhoff in Munich and spent Christmas 1942 there. In the next 18 months we worked at various jobs such as chipping ice from the streets. Our group was finally kicked out of Munich because we were spreading propaganda and so we were sent to Silesia in Poland where we were put to work in the coal mines at Bori. Coal seams were mainly in narrow strips about one metre thick and most of the work was done on our hands and knees. Christmas 1943 was spent in Bori.

The next move was to Mombrova which was suppose to be the biggest and the best mine in the Silesian field. We were still there for Christmas 1944. On New Years Eve I was on afternoon shift and my job was to smash up any lumps of coal bigger than my head with a 4-kilogram hammer. The conveyor belt had broken down and everyone was sitting around waiting for repairs. The foreman came along and started picking on me. After a slight argument he was about to strike me with his walking stick which was shaped like a miner’s pick. So, I gave him a wallop on the earlobe. He went off talking to himself and returned in a few minutes with a rifle and told me to go with him. It was 2 ½ kilometres out to the main head which is a long way when you have a nut with a loaded rifle at your back. On reaching the shaft one of the camp guards was there and escorted me back to the camp where I had to front up to the camp sergeant. He started to scream and yell at me and when I tried to explain to him what had happened, he grabbed the guards rifle slipped a cartridge in the breach and stuck the barrel about six inches from my forehead. I was about to ask him to clean the barrel before he shot me but our interpreter came in on the scene and I lived to see the New Year in.

By this stage the Russians were knocking on the back door so we started the ‘Long March’ of approximately 900 kilometres to the west. The going was very tough. Minus 20-30 degrees, snow and ice. At night we were billeted in farmers barns some only had planks for cladding with gaps up to a centimetre wide. We were only too pleased to keep marching. At one place we came upon a bag of flour hidden in an old sleigh so we nicked about one kilo of it. The next problem was how were we going to cook the stuff? Joe came up with a bright idea. The Huns used to cook up 2 coppers of spuds every night so all we had to do was make a pudding bag and put the pudding in with the spuds. After much head scratching the best, we could come up with was the leg of Joe’s spare underpants for the bag. I came up with antacid powder and Edgar had some raisins. The result was the best Christmas pudding we’d had for years!

Several days later, we pulled into a barn with the usual set up of residence. Stables and shed built in a circle around the manure pit. We were standing around waiting for the spuds to cook when Joe and I noticed there were pigeons in a loft above one of the sheds. We reconnoitered the place out and after it got dark, we made our way up to the loft and each caught a pigeon. Yum! The next morning everyone knew something was wrong as the pigeons were making a great fuss. I had gone to the toilet and then came back everyone was out lining up. I asked Joe what was going on and he said we were being accused with stealing very special carrier pigeons. I asked him if he had ours and he said he was not game to bring them. I had to go and get my gear so I slipped them into my overcoat jacket hoping to get rid of them along the road. However, for our usual 5-minute break we were not allowed to move off the road and when we eventually reached our destination the guards started to search us. I quickly transferred the bodies from my overcoat down the leg of my trousers and who should have to search me? None other than the sergeant who was going to shoot me six weeks before. He spotted blood stains on my overcoat and said “so what have we here?” I pointed to a scab on my hand and said it happened the day before yesterday. He went on to the next chap and looked back at me as if to say he knew who the culprit was. Not wanting to push my luck any further I removed my garters to let the birds out put them back into my great coat and waited until the guards were busy further up the line. I then slipped over to a pile of logs about 4 metres away and pushed what was to have been our tea between the logs.

To finish the journey, we were loaded into open coal trucks 40 men to a truck. The thaw had just started. Forty-eight hours later we arrived in Regensburg. We were billeted in a farm shed approximately 10 kilometres out and spent the next three weeks cleaning up the town. During this time an episode occurred that I will never forget. The farmer who owned the farm where we were billeted accused us of stealing spuds. We were lined up so that the Germans could question us as to who the guard was who let us through the fence. No POW would give the Germans an answer so we were kept standing in line all night in the freezing cold. As we got tired some of us got out of line. I was one of these unfortunates. The next thing I knew I received a severe blow to my tail bone from either a rifle butt or an army boot. I have suffered ever since with pain in my spine which has now turned into chronic arthritis. The next day we were thanked by the guards for not dobbing them in. The Germans changed the guards on us.

The allied Air Force was really on top by this time. They were blanket bombing in close formation and how we ever escaped I don’t know. One afternoon we were walking back to camp because the air raid siren had gone and we wanted to get back out of the town. The first flight came in really low on the eastern horizon and let his eggs go. Then the next right behind and alongside. So, it went on, getting closer all the time. We could see the red flare go up from the flight leader signalling for the flight to drop its cargo of bombs but fortunately for us (about 250 in all) we were now on approximately a hectare of vacant land and the flight that came over us was about 100 metres too long.

The Yank Army was only two days away and we were on the move again. We were given the choice of staying where we were so myself and about 10 others stayed until they arrived. I was able to get a ride back to Luxemburg with Yank transport then several of us caught a train the next day to Brussels where a British air base was close by. We were packed into a Wellington Bomber and I had to lie on the floor around the central gunners’ feet. On arrival in Buckinghamshire we were thoroughly sprinkled with DDT to get rid of the lice which had been our constant companions for four years. We then went down to Eastbourne where we were outfitted in Aussie uniforms and then it was on to Liverpool where we boarded the ‘Dominion Monarch’ bound for Australia via Panama Canal. There was a big contingent of Pommy naval ratings on board and as we passed under the ‘Coat Hanger’ (Sydney Harbour Bridge) one was heard to say “eh by goom they sure have something to skite about”.

At long last our journey took us back across the Nullarbor to Perth where we were discharged.

Return to MEN AT WAR Page

Return to HOME Page

Chris Francis Kealley. Chris Francis Kealley. Chris Francis Kealley. Chris Francis Kealley. Chris Francis Kealley. Chris Francis Kealley.

2 thoughts on “CHRIS FRANCIS KEALLEY”

Thanks for another great story.

Thank you very much for publishing my Dads script of his life in the Army WWll 1939-1945.

I enjoy following your on going work.

Kathy Nice

Comments are closed.