Marshall Family. Marshall Family. Marshall Family. Marshall Family. Marshall Family. Marshall Family. Marshall Family. Marshall Family.

| MENU |

|---|

| SCHOOL DAYS |

| EAST BROOMEHILL SCHOOL |

| MARSHALL SUPER SPREADER |

Broomehill East is a small Western Australian rural Location within the local government area of Broomehill-Tambellup. It is located approximately 278 kms from the capital Perth covering an area of 536.996 square kilometres. Broomehill East has a recorded population of 125 residents.

It’s most famous resident was Arthur Marshall, the inventor of the “Marshall Super Spreader,” who went to school at the East Broomehill school. All that’s now left of the school is a concrete cricket pitch in a paddock.

Below is an extract from:

“Yes… there is life besides cricket!“

An autobiography by Arthur Marshall

Reproduced with permission.

In the years from 1870 to 1883 Mrs Marshall, had eleven children. The two boys born in 1876 and 1877 were Robert Hamilton Marshall and Norman Eugene Marshall. Robert and Norman were born in Tasmania and, in very young life, began working underground in the mines.

They then went to the copper mines at Moonta in South Australia where they met the Jones girls, Lilliot and Cora, who also came from a family of eleven. Robert married Lilliot and Norman married Cora, and they later moved to Kalgoorlie, still working in the mines underground.

Because of poor ventilation in the mines during those times, the two men developed what was known as ‘dust on the lungs.’ Their doctor told them if they went farming, they could continue to live for quite a few more years. In about 1906, they purchased one thousand six hundred acres of land at East Broomehill. The farm was named “Tama Grove.”

Before white man came and destroyed it, the country had a lot of beauty to be seen. Even so, Marshall brothers would have only seen endless work. They had left their wives and families in Kalgoorlie, whilst they got to build two houses out of material they could find in the bush. These were small houses, one house of two rooms and the other of three rooms, with walls made of ‘wattle and daub.’ Poles were erected about six feet apart and round mallet sticks were hammered in to either side. This was then packed with mud for the walls and a roof of galvanised iron was nailed onto round timber framework. When the house was completed the wives and children came to join their men.

While one house had a wood stove in it, the other only had an open fireplace and everything had to be organised so each house could use the stove for baking bread or having a roast dinner. It seemed to work quite well.

Robert and Lilliot had eleven children, and Norman and Cora had three. Both lost one child at birth. These babies were buried on the farm, but to this day, the parents were the only ones who knew where were buried. On April 21st, 1922, Lilliot gave birth to her ninth baby, Arthur.

.

SCHOOL DAYS

The school that Arthur attended at East Broomehill was very small, like most bush schools were in those times, seating a maximum of sixteen children. It was made of weatherboard and asbestos, with an open fireplace and two one-thousand-gallon tanks for drinking water. It was situated on a watershed, which meant that the water ran in two different directions. On the south side it ran down to the Pallinup River, which was quite a few miles away, and to the north it ran into creeks that ran through Tama Grove. The water then eventually finished in the Coyrecup Lakes, which were about fifteen miles away.

The view to the south was magnificent. It went across miles of farmland to the Stirling Ranges that stood out in different blue colours ranging from light to a very deep blue, depending on the atmosphere of the day. If it was stormy weather, the mountain peaks would be a really deep, dark colour.

In the early summer months, the farming country was interspersed with Cape weed flowers. These paddocks would be a hundred or more and were spread here and there over miles. You could see all of this from the school window while sitting at our desks. Whoever had the foresight to build in such a position must have given it a lot of consideration.

Mr G A Thomson bought the farm next door to us, he spoke of his first introduction to the Marshall kids as “small urchins jumping on something in one of his paddocks.” He rode his horse believe what he was seeing. There were these kids jumping on a half dead snake. They had back with a stick and then were finishing it off by jumping on it.

School was an introduction to a different life. I wasn’t quite six years old when I was sent to school early because there had to be at least eight children attending school to keep it open.

Our mode of transport over the three and half miles was by horse and cart using a semi draught horse. He was given to dad and uncle by another farmer for the kids to use to take to school and was named General. He was only a youngster, about three years old, and he went back and forth to our little school from the day it opened in 1918 until my youngest sister was the last Marshall to attend in 1939. He was then turned out to graze and my sister and I bike from then on. So, he went up and down that road for twenty years, sometimes going at his own pace even without reigns to steer him while the kids sat on the floor of the cart playing some game or other.

My first recollection of school was a low desk with a bench type seat to sit on. Now, I was the only new student in that year of 1928 and after doing some work for about an hour my teacher would tell me to put my head down on the desk and have a sleep until morning playtime.

I was born left-handed. My first evening home after the day at school my father said to me, “What hand are you using for writing at school?” When I told him it was my left hand he said, “Tomorrow, first thing, you tell your teacher you are to be taught to write only with your right hand.” I have always been thankful to my father for that advice.

In the playground, the big kids called my first teacher by the nickname of Cyclops. Thinking that this was his true name and in answering a question from him, I called him by that name. He said to me, “What did you call me?” Being brought up to always respect my elders I said, “I’m sorry Mr Cyclops.” His correct name was Mr Brookhouse. Not really a very good way to start one’s school life.

I took to being educated with a lot of energy, enjoying trying to overcome subjects and to learn what they meant. My favourite subjects were maths, history, geography and reading. Being in the days of ink well, my writing pad was always in a terrible mess with spots everywhere. The subject of English was something like singing to me, and I just couldn’t grasp it.

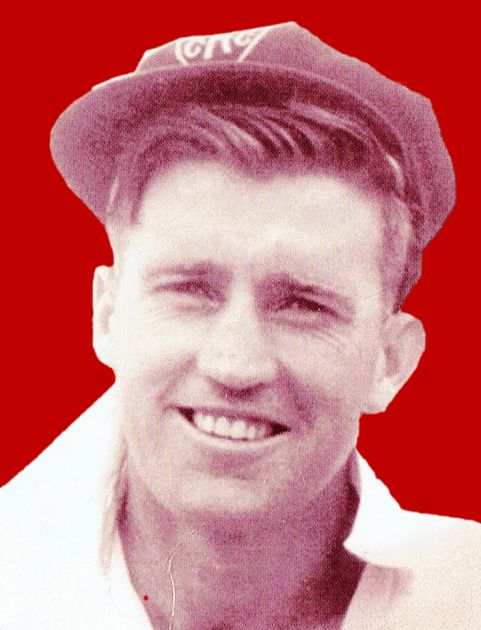

Arthur Marshall during his cricketing days in Harvey

Arthur at Country Week playing for Harvey in the late 40’s/early 50’s.

We used to have an end of year concert when parents and friends were invited to the school and there would be supper afterwards. It was a real social event because farmers rarely had time to get together. For one item all of the children in the school would sing was the opportunity I had waited for. I was really excited being on the stage, when right in the middle of a song teacher whispered quietly to me to just open my mouth and close it without making a sound. My whole world fell in. I still feel inadequate today when people start talking about singing.

One male teacher didn’t seem to have much hope for me. He used to call me Brains (that is if you have any). He was a bit of a sadist, but still a good teacher. One day he called out to me, “Brains, come out to the front of the class.” Then he lined up the other kids, all eleven of them, and said, “Here is the cane, Brains, now give each student one cut.” I really felt top of the class giving each child a good whack Then he said, “Hold out your hand and each one can give you a cut.” I held back tears for as long as I could, then they flooded out. I still had to have those eleven cuts. Bless him.

One teacher we had, had children of her own. This meant that she understood what kids get up to. One day she passed small slates around to the bigger kids and said, “I want you to draw me a game of cricket. A slate was about two feet by one foot in size, made of black slate, and white chalk was used to write on it. We thought this was great and there was complete silence as the drawings were done.

When everyone had finished, our teacher surveyed each one and commended us on our good work. Then she said, “Who put the boots on the fieldsmen?” Frank, my brother, put up his hand and said, “I did teacher.” The teacher said, “Come out to the front Frank and hold out your hand.” She gave Frank six cuts of the cane. Frank was then told to take a wet rag and go and wipe the cricket field off the back of the boys’ toilet. Mrs Peacock, the teacher, sure was a shrewd one. Not one of us, if asked, would have owned up. Yes, this was because she had children of her own and she understood how things worked with us kids.

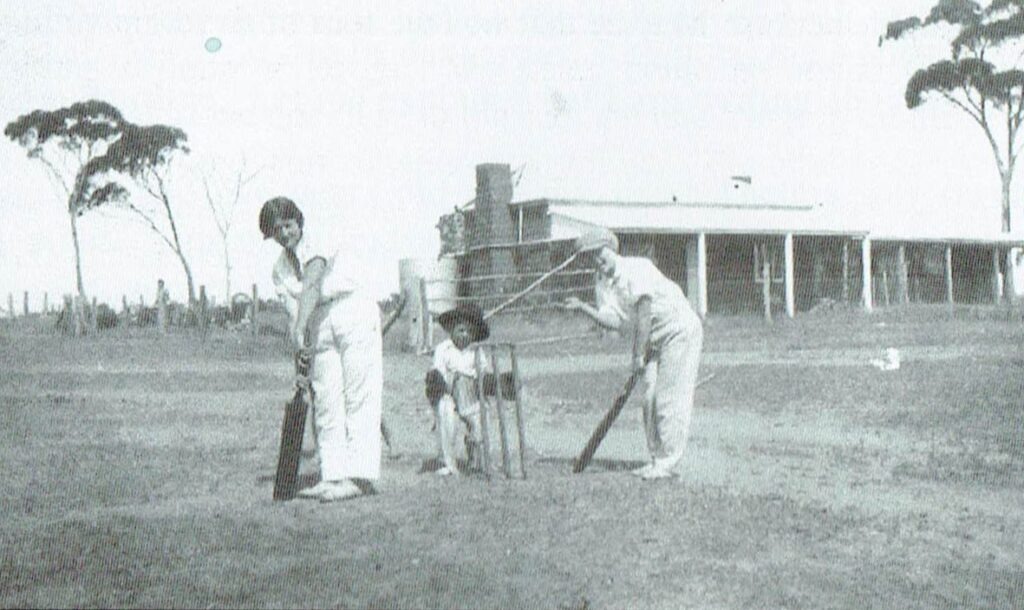

Playing sport has always been a big part of my life and at school every chance we got, we were playing some form of cricket. Little cricket with part of a broom handle for a bat, or cricket with a bat and ball. We played on the oval near our school, although in reality the oval was only part of a farmer’s paddock with a concrete wicket put down on it.

Thelma Roberts (nee Marshall) was the wicket keeper for the school for a time and then, as she grew older, the female teacher thought she should give up cricket. The boys couldn’t understand why, as she was so good behind the stumps!

The three Marshall girls playing cricket at the East Broomehill school

Being only a small school, cricket was the natural game to play, and play it we did. The result was the best school team in the area, and in all the years I was at school we only lost one game and that was against Katanning, which was a school of five hundred children. We broke even by winning one game and losing one. Gnowangerup State School, which opened in November 1908, with over one hundred children, never won a game against us. Broomehill School, also with one hundred plus children, didn’t worry us. It was against Broomehill when I was about eleven years old that my classmate and I made a one- hundred partnership. Ron got fifty-four runs and I made forty-six. Cricket you will see has always been a major part of my whole life, starting interschool cricket in 1932 and playing my final game at Capel in a Grand Final in 1989.

I never did take my Junior Certificate. About a month before exams started, we were cutting hay at home and I left school to give a hand with the harvest. While I spent my years at school, life went on as usual at home.

During World War Two, Arthur Marshall joined up in 1941 and was a 2/2nd commando fighting the Japanese in East Timor and New Guinea.

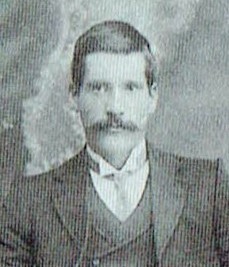

Robert Hamilton Marshall

Robert Hamilton Marshall was born in Tasmania and left school to start working in mines in there before moving to Moonta in South Australia. Robert and Norman met sisters Lilliot and Cora Jones in Moonta, and were married before moving to Kalgoorlie. He worked with his brother Norman in the mines there. But, because of poor ventilation in the mines during those times, the two men developed what was known as ‘dust on the lungs.’

So around 1906, with his brother Norman, they purchased one thousand six hundred acres of land at East Broomehill. The farm was named “Tama Grove” which they, after many long hours, the two men turned into a productive state.

Robert and Lilliot had eleven children while Norman and Cora had three. Both lost one child at birth. Lilliot passed away in 1928 and Robert in 1935. Robert’s children consisted of Robert Charles, Clarence John James, Dorothy May, William Matthew, Clematis, Francis, Thelma Marie, Arthur, Morris Leslie, Helen Elizabeth and an unnamed baby boy who was stillborn.

Robert also spent many years as a member of the Broomehill Road Board.